I first came across Roman Vishniac’s book A Vanished World as a child, seeing it prominently displayed on a family friend’s bookshelf. The striking and sensitive black-and-white documentary photographs of people who seemed somehow both foreign and familiar commanded my attention. Even at that age, I understood their significance.

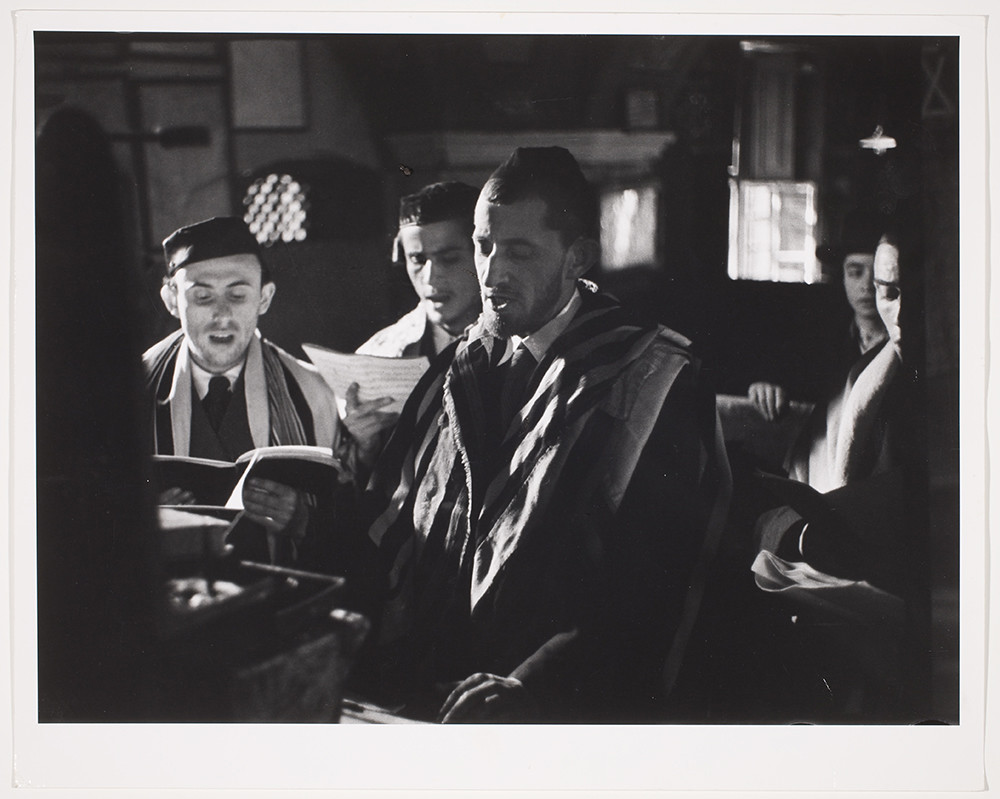

Vishniac’s photographs comprise an intimate record of the final moments of Eastern European Jewish communities before the Holocaust. His images record life in the villages and ghettos from which so many fled persecution—and from which so many did not escape. Being Jewish himself and living in Berlin at the time, he imbued his photos with a great deal of sensitivity and understanding.

An excellent new documentary about Vishniac’s life and career, directed by Laura Bialis and simply titled Vishniac, tells the story of the man behind the photographs from the perspective of his daughter, Mara Vishniac Kohn. She took up the task of managing Vishniac’s photographic archive after his passing in 1990. (Initially slated to be acquired by the International Center of Photography, it is now housed as part of The Magnes Collection at Berkeley.)

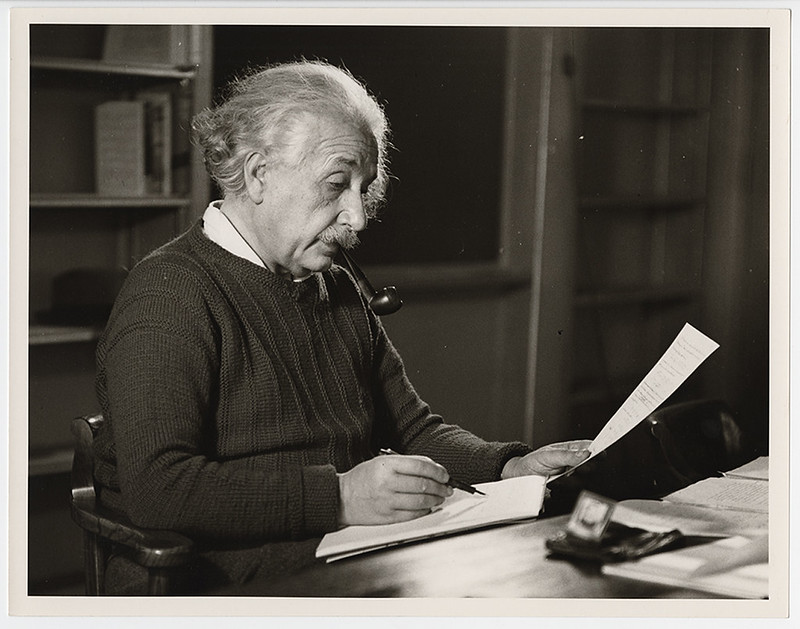

Bialis moves quickly through Vishniac’s turn-of-the-century Russian childhood to his early adult life. As a young boy with a keen interest in science and biology, Vishniac became enamored with taking photographs through his microscope – his earliest attempts to document worlds largely hidden from view. In the 1920s, forced to flee Russia, Vishniac moved his wife and two children to Berlin, where he discovered Modernist photography and began capturing life on the street in stark, dramatic tones.

In the early 1930s, with Nazism fast on the rise, he started surreptitiously documenting the anti-Semitic propaganda spreading throughout Berlin. Mara relates that in order to avoid attracting suspicion, he would bring her along and have her pose for the camera, so that it would seem like he was simply taking a snapshot of his young daughter. In a journal entry, conveyed effectively via voice-over, Vishniac refers to a shop selling bogus craniometric instruments to supposedly prove one’s Aryanism as “the height of lunacy.” Vishniac’s shift towards a more socially conscious perspective leads up to the landmark body of work that ultimately became A Vanished World.

First, however, the film first takes a more personal turn. Mara reveals that during this time, her parents were struggling to hold their relationship together—and that her father had begun a passionate affair with a German woman named Edith. It’s a poignant story about parents who grow apart and the toll that it takes on the children. But the way this family drama unfolds during such an extraordinarily tumultuous era gives it greater significance. Under newly passed Nazi laws, the affair becomes a criminal act. After Kristallnacht, the family strives to seek asylum elsewhere. In one of the most moving segments in a film that has no shortage of such moments, Mara discusses the Vishniacs’ efforts to emigrate to America and provides a window into how difficult it was for German Jews to leave the country at that time.

Fortunately – spoiler alert – the family made it to America, arriving in New York on New Years Eve 1940. From there, Bialis fills in the lesser-known aspects of Vishniac’s biography as he rebuilt his life and career yet again. She also chronicles his children’s entrance into adulthood.

Once settled in America, Vishniac returned to his early childhood interest in biology and photomicroscopy. He made several breakthroughs in the field of scientific photography, became a contributor to Life Magazine, and appeared in a series of short educational films that explored “the big little world of Dr. Roman Vishniac.” He also developed a close friendship with Magnum photographer and International Center of Photography founder Cornell Capa, which led to the rediscovery and renewed appreciation of his photographs of Eastern European Jewish life.

Deftly interweaving these strands into the larger story, the director tells a tale about Jewish life during the early-mid 20th Century that celebrates the value of photography. Ultimately, this absorbing documentary is a portrait of a family just as much as it is a portrait of an artist. And it makes a strong and compelling case for Vishniac’s inclusion in the canon of great 20th Century photographers.

Vishniac (directed by Laura Bialis). Color, 95 min., 2023.