Photographers as Filmmakers is a series that explores films made by iconic photographers.

“All through the years, people have said, ‘you should make a film,’ or ‘aren’t you thinking about making a film, because it seems a natural next step?’ But I never wanted to work with a crew, since I don’t like to work with other people. I like having full control of what I’m doing. If you’re making a film, you give up control.” – Cindy Sherman

In 1997, Cindy Sherman released her first—and, to date, only—feature film. By that time, Sherman was already well-established as a master of the photographic self-portrait, revered in art schools, and internationally renowned to such an extent that she bordered on household-name status. That same year, MoMA mounted an exhibit of the complete Untitled Film Stills (sponsored by pop icon Madonna) and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles debuted a mid-career retrospective of Sherman’s work. At the pinnacle of her fame, Office Killer, an underachieving arthouse horror-comedy, undercut her reputation like a letter-opener to the jugular. Rejected by both critics and audiences, the film has since been largely disowned by Sherman and relegated to the pop-culture scrap heap.

That’s too bad because the truth is, it’s not nearly as bad as its notoriety suggests. It may not be a great film, or even a particularly memorable one, but it’s entertaining. It stays true to the rules and conventions of the horror genre while finding interesting and inventive ways to color in-between the lines.

Screen legend (and national treasure) Carol Kane stars as Dorine, a high-strung oddball working as a copy editor for a Consumer Reports-style magazine called, in a tame attempt at satire, Constant Consumer Magazine. The magazine is in the process of downsizing, and as the movie begins, Dorine receives a memo informing her that she will soon be working remotely part-time.

This is a blow to Dorine, in more ways than one. When not at the office, she’s stuck taking care of her ailing, verbally abusive mother, and she doesn’t seem to relish the idea of spending more time at home.

For the time being, however, she’s finishing out her week in the office. One night, while working late, she accidentally electrocutes her sleazy boss. (The scene seems intended to be comedic, but it plays out in rather gruesome fashion.) She then decides to cover up his death, transporting his body to her house and stashing it in the basement rec room. When she literally gets away with murder, she begins targeting anyone in the office that she believes deserves to be punished. As more co-workers disappear, she gets rewarded with greater opportunities at the magazine, and the basement gets a little more crowded with new “friends.”

Meanwhile, several writers for the magazine, Norah and Kim, along with Norah’s boyfriend and office IT guy Daniel, are trying to figure out why their co-workers and supervisors are suddenly MIA. Slowly, they begin to suspect that Dorine might have something to do with it.

Sherman assembled an incredibly talented cast for her feature debut. It’s impossible to overstate how good Kane is in the role. There’s also Jeanne Tripplehorn as Norah, future Sopranos star Michael Imperioli as Daniel, Fassbinder favorite Barbara Sukowa as their overbearing, chain-smoking, “Devil Wears Prada”-type boss, and an uncredited Eric Bogosian as Dorine’s creepy stepfather. But the standout performance belongs to former 80s teen icon Molly Ringwald as Kim, Norah’s friend and co-worker. Ringwald takes an underwritten supporting role and transforms it into a memorable and relatable character, ultimately emerging as the de facto protagonist seemingly through sheer force of will.

The pedigrees on the other side of the camera are equally impressive. Todd Haynes helped with the screenplay just a few years before being nominated for a screenwriting Oscar for Far from Heaven. Evan Lurie (brother of John and former Lounge Lizard pianist) composed the offbeat, memorable score. Good Machine (the A24 of its era) was the production company, and Miramax handled distribution.

Still, despite all the talent, it falls short of the mark. Technically billed as horror-comedy, it’s more quirky than comedic, likely the result of blending two disparate visions. The principal screenwriters (Elise MacAdam and Tom Kalin) seem to be aiming for something tonally lighter and campier, while Sherman is more interested in surrealism and the grotesque. As a result, the film seems a little at odds with itself.

Similarly, despite the title, it’s not really a workplace satire. It’s a character study, a dissection of feminine archetypes, and an exploration of gender and power dynamics. In these ways, it’s totally of a piece with Sherman’s photographic oeuvre.

To that point, the film nicely subverts typical gender roles by transforming poor, helpless Dorine into an unstoppable superhuman killing machine. However, Sherman’s major miscalculation is making Dorine the main character. As in many of her self-portraits, Sherman places an eccentric caricature front and center. But ironically, what makes those images so compelling is ultimately what hamstrings the movie. Dorine, with her off-putting personality and mannerisms, works best in small doses. (The unnecessary reveal midway through that she was a nepo hire only further alienates her from the audience.) Making a more “normal” character like Tripplehorne’s Norah or Ringwald’s Kim the lead would have given the audience a character they could more easily root for and relate to. Then again, Sherman has never concerned herself much with relatability.

Dorine definitely belongs in the pantheon of Sherman’s creations. Like many of the director’s photographic personas, Dorine styles herself according to an outdated, overly-romanticized ideal of feminine glamour and makes herself look even more bizarre in the process. It’s hard not to focus on her unevenly drawn-on arched eyebrows that do little to hide her actual eyebrows. The same goes for her tightly parted half-bun hairstyle, her large octagonal glasses, and her frumpy office wear. The other characters’ fashion choices are culturally coded in retro-cool ways. Norah’s pink suit is reminiscent of Jackie-O’s iconic look, for instance, while Kim’s style is modeled on 60s Italian couture. (That office has quite a dress code.)

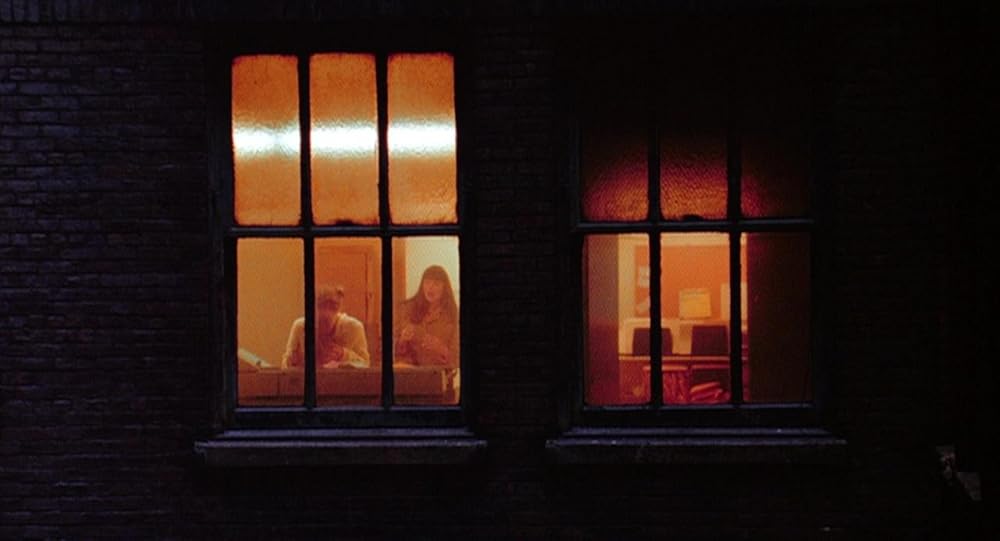

If turning screentime into Dorine Time is what threatens to drag the film down, the visual aspects of the film are what redeem it. Sherman, working closely with cinematographer Russell Lee Fine, proves herself an innovator in terms of composition, light, and color. The shots she designed draw more prominently from photography’s lexicon than cinematography’s.There is a great deal to study and admire in terms of the careful framing, the color palette, and the mise-en-scènes, all of which reveal an artist consciously avoiding cliches.The camerawork is often quite original—and at times inscrutable, in the best possible way. Who else but an art photographer would choose to shoot a dramatic scene from a distance, framed through a window and slightly obscured, for largely aesthetic reasons? But her left-field choices work, in part because they are both wonderfully innovative and aesthetically appealing.

The cinematography elevates the material. Midway through the film, there’s an exceedingly slow take, as Dorine’s wheelchair-bound mother slowly ascends to the second floor on a stairlift while Dorine, in the background, busies herself in the kitchen. As the elderly woman rises, the light changes on her until she’s in full silhouette. The camera remains fixed on this moment even as the doorbell rings in the background. The frame is nicely bisected, and the decor gives the viewer a window into these characters’ lives. Everything is exactingly arranged, including the electric candlestick on the far right casting a macabre shadow. It’s mesmerizing.

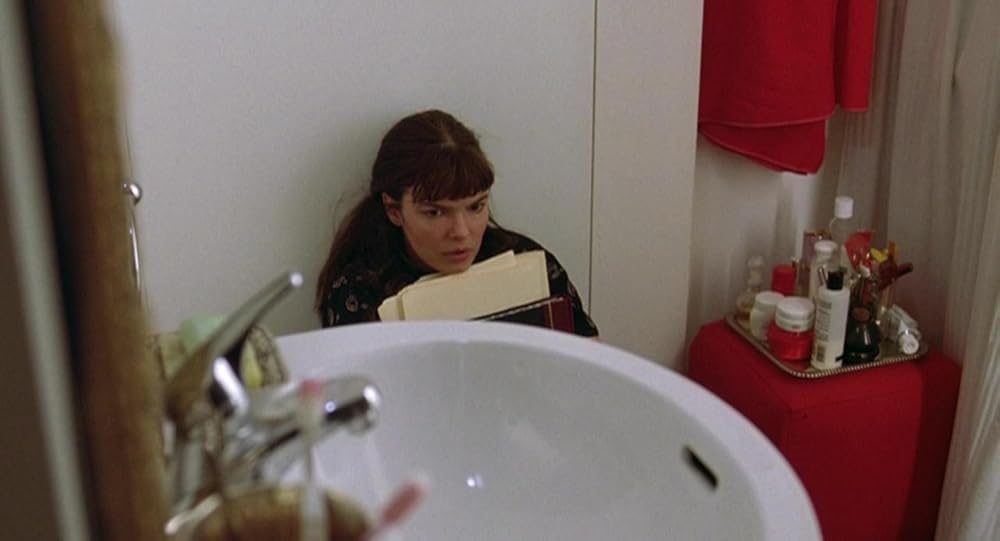

Likewise, the two (untitled) film stills below could be right at home on a gallery wall. Note the ways they both make use of primary colors such as red, white, and yellow. They are pop art in the best sense of the term. Each image is evocative, adding layers of depth and meaning to scenes that, on the page at least, don’t have all that much substance to them.

For the visual aesthetic alone, Office Killer is worthwhile viewing for photographers. Had Sherman chosen to make an abstract experimental film—or had she chosen to create an installation of still images like the ones above and ditched the plot and dialogue—I could see this being one of her more celebrated works. Going against expectations, perhaps, she decided to do a more commercial project, and it ultimately got the better of her.

But for a first-time filmmaker in her 40s unaccustomed to collaborating with others and learning the ropes as she went along, she nevertheless acquitted herself nicely. In a way, this is her student film. I can’t help but wonder what her sophomore effort could have been, had she stuck with it, but movie-making ultimately proved antithetical to her creative process.

In the end, Office Killer is the kind of movie that’s more likely to have defenders rather than fans. It may not reach the high bar set by Sherman’s still photography, but it’s right in line with late-night basic-cable fare that you might pause on while channel surfing. It’s female-driven horror at a time when that was a rarity. And it’s at least as entertaining as a lot of the streaming content being churned out these days. Faint praise, perhaps, but sometimes that’s enough.

Office Killer (directed by Cindy Sherman). 35mm (color), 82 min., 1997.