About a month ago, I rewatched Scorsese’s 1985 dark comedy After Hours and it struck me that SoHo, depicted in the film as a bohemian wonderland / Dante’s inferno of artists, musicians, S&M devotees and Mister Softee truck drivers, currently boasts the most exorbitant real estate in New York, one of the most expensive cities in the world.

As unlikely as it seems, some of that rough-around-the-edges bygone boho sensibility has managed to survive the massive sea change of redevelopment. It is both surprising and comforting to learn that there are still artists and musicians living and working in SoHo, TriBeCa, midtown Manhattan and similar parts of the city. This is thanks to something colloquially known as Loft Law, from which photographer Joshua Charow’s debut monograph takes its title. Charow’s book profiles the last remaining holdouts benefiting from this early 1980s ordinance that paved the way for rent stabilization in a dynamically changing city. In words and pictures, he surveys dozens of artists who somehow managed to survive the commercialization and gentrification that completely transformed a number of neighborhoods throughout Manhattan and Brooklyn.

Charow’s preface explains the significance of Loft Law in greater detail. It also delves into his research process and tenacious doorbell-ringing approach that gave him the opportunity to visit these artists’ home studios. From there, the book is a whirlwind tour of everyone who let him in the door.

Ultimately, Loft Law is a story about artists and their relationships to the spaces where they live and work. It also serves as a kind of primer to some of the key figures in the city’s experimental art, film, and music scenes over the past several decades. Take just the first three featured in the book: pioneering avant-garde filmmaker Ken Jacobs, A.I.R. Gallery founder Loretta Dunkelman and influential composer, musician, and multimedia artist Phillip Niblock.

The book celebrates these artists’ life’s work and dedication to their calling—not just their shared commitment to affordable housing in formerly industrial buildings that once lacked plumbing and electricity. It’s an invigorating rediscovery of the city’s creative spirit that has been pre-emptively eulogized so often throughout the years. Here is proof that it hasn’t been completely displaced yet.

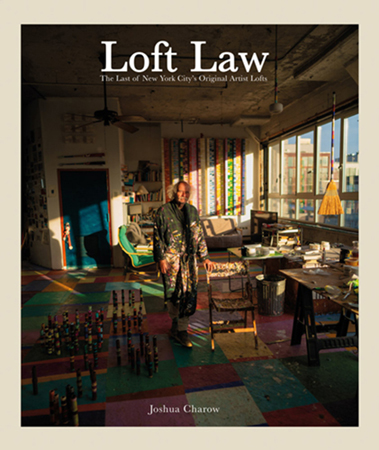

Individuals and couples are introduced by name and occupancy (the neighborhood and the year they moved in) – for instance, “Loretta Dunkelman, Occupancy: The Bowery, 1966.” In short text passages, the tenants reflect on their years in their lofts. Around five or six photos accompany each entry. These tend to be a combination of portraits, interiors, detail shots that often showcase artwork in situ, and what might be termed “hero shots” – main overviews of the space, usually with the artists themselves posing in the middle, at a distance from the camera. (A documentary filmmaker as well, Charow also made short films profiling the artists in tandem.)

Overall, the images can come across as a bit pedestrian, both as portraits and as architectural photos. However, this is a case where the subject matter and the storytelling take precedent over the aesthetics. It’s a great story well-told and it enshrines a part of NYC history that might otherwise go undocumented—or at the very least, underdocumented.

One of the more playful and dynamic images, framed as a vertical medium-length portrait, finds the photographer on the wrong end of a baseball bat wielded by wild-haired, mustachioed painter Steve Silver, standing in the center of his studio—no caption necessary. I would have loved to see more of these types of photos that deviate from the formula. (Incidentally, a different picture of Silver appears on the book cover—he’s just that photogenic.)

The book’s design is highly effective, both visually and conceptually. Charow’s research led him to the New York City Municipal Archive where he was able to track down blueprints of each building. Facsimiles of the layouts for each loft are incorporated into the white space framing the photos and text. It’s a fantastic touch that elevates the work tremendously.

Given the overwhelming emphasis on youth subcultures in contemporary photography, it’s refreshing to hang out with some old souls for a change. And make no mistake, there are no uninteresting stories here. All of these artists are worth spending time with and learning about—one loft at a time.

Loft Law: The Last of New York City’s Original Artist Lofts by Joshua Charow. Damiani Books, 2024. 192 Pages, 108 Photographs. Hardcover.